Foranderligheden er ordenes natur

IT IS THE NATURE OF WORDS TO CHANGE

ENGLISH TRANSLATION IN ITALICS

Jeg forsøgte. Forsøgte vitterligt at læse D.H. Lawrence og hans Lady Chatterley's Lover naturligvis. Det er dog sommer. Men han er præcis så skematisk, som jeg husker ham. Ironiserende med et persongalleri af karikaturer. Han holder ikke af sine egne personer, og hvorfor skal vi andre så spilde vores tid?

Den evige kunsthistorikertvivl slog derfor ned, om man kan vide for meget om kunstens samtid? Om det er muligt at kende for meget til bevæggrunde, fuger og lim til kunstværket, så det ikke længere er muligt at være til stede helt og fuldt sammen med det?

Jeg blev tidligt ramt af Bloomsbury, den gruppe af kunstnere og intellektuelle i det tidlige 1900-tal, som D.H. Lawrence forgæves forsøgte at blive en del af. Hans taktik var heller ikke videre gennemtænkt. Han jamrede og klagede sig over sin vanskæbne, hvad der kun fik forbillederne til at trække på skuldrene af ham. I næste led ironiserede han over dem, beskrev dem som fritænkere med uanede mængder af ord, men grundlæggende tomme ud over - ordene.

Det var de samme mennesker, som var engagerede i verden omkring dem til deres sidste åndedrag, så jeg vendte tilbage til Virginia Woolf for at genlæse, hvad hun i grunden skrev om sin kollega. D.H. Lawrence var og blev en stakkel i hendes øjne.

For hun fremhæver de mange ords rigdom. Hvad hans hensigt har været, undrer hun sig, med kun at bruge 6 ord af det engelske sprog, når nu det er 1 mio. af dem? Og dog var det netop hans hensigt, hans kald som prædikant, at måle alting ind med en lineal. Der var et bevis at finde. Hun måtte konkludere goldheden i hans projekt, hvor let det var at finde sig en genvej, frem for at gå udenfor og indtage verdens mangfoldighed, før han påtog sig at fælde dom.

I tried. I tried indeed to read D.H. Lawrence and his "Lady Chatterley's Lover", of course. It is summer, after all. But he is as schematic as I remembered him. Ironic with a gallery of caricatures for characters. When he has no love for his own characters, why should the rest of us waste our time in their company?

The art historian's all too usual sad reflection struck me, whether one can know too much of the times in which the artwork came about? Whether it is possible to know too much about motives, exposing the joints and glue within the finished artwork making it no longer possible to be fully present with it?

I succumbed from a very young age to Bloomsbury, the group of artists and intellectuals in the early 1900s, of which D.H. Lawrence attempted to become a part. Without success. In any case his tactics were not exactly well thought out. He incessantly lamented his misfortune, which only served to make his role models shrug their shoulders. Later on he ironized all they stood for, describing them as free thinkers juggling an unlimited amount of words, but basically empty excepting – those very words.

They were the very same personalities, who were engrossed in the world around them to their last day in life, so I returned to Virginia Woolf to reread what she herself wrote about her colleague. To her eyes D.H. Lawrence was and remained a poor thing.

For her part she highlights the wealth constituted by the many words. What could his intention have been, she was wondering, using only six words in the English language, when there are a million of them? And yet it was precisely his intention, his calling as a preacher, to measure everything with a ruler. There was proof to find in this. She had to conclude the barren greatness of his project, how easy it had proved to take a shortcut, rather than going outside and take in the diversity of the world before he took it upon himself to pass judgment.

Da hun skrev dette, havde han længe været død, og enhver mulighed for at blive gammel og vis udelukket for ham. Der er derfor ingen grund til at spekulere over mulig overhobning af viden om en samtid bag et værk, lad os i stedet dykke ned lidt flere ord, disse de vildeste, frieste og mest uansvarlige af alt.

- "Selvfølgelig kan vi fange dem ind og sortere dem og placere dem i alfabetisk orden i ordbøger. Men ord lever ikke i ordbøger, de lever i vores sind. Og dér lever de lige så forskelligt og mærkeligt, som mennesker lever, når hid og did, forelsker sig og parrer sig", som Virginia Woolf folder ud i den eneste bevarede optagelse af hendes stemme:

When she wrote this, he had been long gone, and thus refused the opportunity to grow old and wise. For the same reason there is no reason to speculate about the possibility of amassing too much knowledge about the time and day of an artwork; let us rather dive into a few more words. Words: The wildest, freest and most irresponsible we have.

"It is only a question of finding the right words and putting them in the right order. But we cannot do it because they do not live in dictionaries; they live in the mind. And how do they live in the mind? Variously and strangely, much as human beings live, ranging hither and thither, falling in love, and mating together", as Virginia Woolf unfolds in the only surviving recording of her voice:

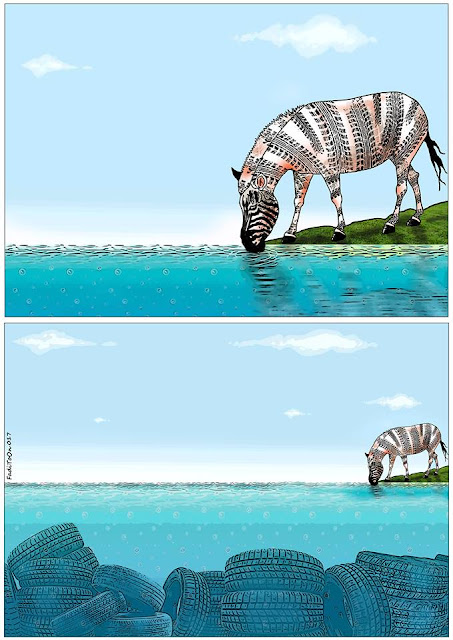

Hun læser fra "Craftmanship", der siden blev udgivet i essaysamlingen The Death of the Moth. Inspiration også til at sætte ord på bladtegningen, hvordan den tilsyneladende enkle stregform er i stand til konstant fornyelse og dog med de mange lag i sig:

"Ord, engelske ord er fulde af ekkoer, af erindringer, af associationer. De har været langt omkring, på menneskers læber, i deres hjem, på gaderne, på markerne, gennem så mange århundreder. Og det er en af de store problemer ved at skrive dem i dag - at de har oplagret andre betydninger i sig, andre erindringer, og de er indgået i så mange berømte ægteskaber i fortiden".

Foranderligheden er ordenes natur - som den er tegningens. Så hvorfor - for nu at afrunde med hendes undren over D.H. Lawrences projekt, hvorfor hans kritik af en lang række mennesker som urene, hvorfor ikke et system, der indbefatter det gode? Det ville have været et virkeligt nybrud: Et system, der ikke udelukkede.

She is reading from "Craftsmanship", which was eventually published in the essay collection "The Death of the Moth". Inspirational too in putting words on the cartoon, how the seemingly simple line is capable of constant renewal and yet with the many layers within:

"Words, English words, are full of echoes, of memories, of associations. They have been out and about, on people's lips, in their houses, in the streets, in the fields, for so many centuries. And that is one of the chief difficulties in writing them today – that they are stored with other meanings, with other memories, and they have contracted so many famous marriages in the past".

It is the nature of words to change – as it is to the drawn line. So why - to round off with her astonishment at DH Lawrence's project, his criticism of a wide range of persons as being soiled, why not a system that includes what is good? It would have been a true breakthrough: An inclusive system.

The cartoon shown is courtesy of Per Marquard Otzen and must not be reproduced without his permission.

ENGLISH TRANSLATION IN ITALICS

Jeg forsøgte. Forsøgte vitterligt at læse D.H. Lawrence og hans Lady Chatterley's Lover naturligvis. Det er dog sommer. Men han er præcis så skematisk, som jeg husker ham. Ironiserende med et persongalleri af karikaturer. Han holder ikke af sine egne personer, og hvorfor skal vi andre så spilde vores tid?

Jeg blev tidligt ramt af Bloomsbury, den gruppe af kunstnere og intellektuelle i det tidlige 1900-tal, som D.H. Lawrence forgæves forsøgte at blive en del af. Hans taktik var heller ikke videre gennemtænkt. Han jamrede og klagede sig over sin vanskæbne, hvad der kun fik forbillederne til at trække på skuldrene af ham. I næste led ironiserede han over dem, beskrev dem som fritænkere med uanede mængder af ord, men grundlæggende tomme ud over - ordene.

Det var de samme mennesker, som var engagerede i verden omkring dem til deres sidste åndedrag, så jeg vendte tilbage til Virginia Woolf for at genlæse, hvad hun i grunden skrev om sin kollega. D.H. Lawrence var og blev en stakkel i hendes øjne.

For hun fremhæver de mange ords rigdom. Hvad hans hensigt har været, undrer hun sig, med kun at bruge 6 ord af det engelske sprog, når nu det er 1 mio. af dem? Og dog var det netop hans hensigt, hans kald som prædikant, at måle alting ind med en lineal. Der var et bevis at finde. Hun måtte konkludere goldheden i hans projekt, hvor let det var at finde sig en genvej, frem for at gå udenfor og indtage verdens mangfoldighed, før han påtog sig at fælde dom.

I tried. I tried indeed to read D.H. Lawrence and his "Lady Chatterley's Lover", of course. It is summer, after all. But he is as schematic as I remembered him. Ironic with a gallery of caricatures for characters. When he has no love for his own characters, why should the rest of us waste our time in their company?

The art historian's all too usual sad reflection struck me, whether one can know too much of the times in which the artwork came about? Whether it is possible to know too much about motives, exposing the joints and glue within the finished artwork making it no longer possible to be fully present with it?

I succumbed from a very young age to Bloomsbury, the group of artists and intellectuals in the early 1900s, of which D.H. Lawrence attempted to become a part. Without success. In any case his tactics were not exactly well thought out. He incessantly lamented his misfortune, which only served to make his role models shrug their shoulders. Later on he ironized all they stood for, describing them as free thinkers juggling an unlimited amount of words, but basically empty excepting – those very words.

They were the very same personalities, who were engrossed in the world around them to their last day in life, so I returned to Virginia Woolf to reread what she herself wrote about her colleague. To her eyes D.H. Lawrence was and remained a poor thing.

For her part she highlights the wealth constituted by the many words. What could his intention have been, she was wondering, using only six words in the English language, when there are a million of them? And yet it was precisely his intention, his calling as a preacher, to measure everything with a ruler. There was proof to find in this. She had to conclude the barren greatness of his project, how easy it had proved to take a shortcut, rather than going outside and take in the diversity of the world before he took it upon himself to pass judgment.

Da hun skrev dette, havde han længe været død, og enhver mulighed for at blive gammel og vis udelukket for ham. Der er derfor ingen grund til at spekulere over mulig overhobning af viden om en samtid bag et værk, lad os i stedet dykke ned lidt flere ord, disse de vildeste, frieste og mest uansvarlige af alt.

- "Selvfølgelig kan vi fange dem ind og sortere dem og placere dem i alfabetisk orden i ordbøger. Men ord lever ikke i ordbøger, de lever i vores sind. Og dér lever de lige så forskelligt og mærkeligt, som mennesker lever, når hid og did, forelsker sig og parrer sig", som Virginia Woolf folder ud i den eneste bevarede optagelse af hendes stemme:

When she wrote this, he had been long gone, and thus refused the opportunity to grow old and wise. For the same reason there is no reason to speculate about the possibility of amassing too much knowledge about the time and day of an artwork; let us rather dive into a few more words. Words: The wildest, freest and most irresponsible we have.

"It is only a question of finding the right words and putting them in the right order. But we cannot do it because they do not live in dictionaries; they live in the mind. And how do they live in the mind? Variously and strangely, much as human beings live, ranging hither and thither, falling in love, and mating together", as Virginia Woolf unfolds in the only surviving recording of her voice:

Hun læser fra "Craftmanship", der siden blev udgivet i essaysamlingen The Death of the Moth. Inspiration også til at sætte ord på bladtegningen, hvordan den tilsyneladende enkle stregform er i stand til konstant fornyelse og dog med de mange lag i sig:

"Ord, engelske ord er fulde af ekkoer, af erindringer, af associationer. De har været langt omkring, på menneskers læber, i deres hjem, på gaderne, på markerne, gennem så mange århundreder. Og det er en af de store problemer ved at skrive dem i dag - at de har oplagret andre betydninger i sig, andre erindringer, og de er indgået i så mange berømte ægteskaber i fortiden".

Foranderligheden er ordenes natur - som den er tegningens. Så hvorfor - for nu at afrunde med hendes undren over D.H. Lawrences projekt, hvorfor hans kritik af en lang række mennesker som urene, hvorfor ikke et system, der indbefatter det gode? Det ville have været et virkeligt nybrud: Et system, der ikke udelukkede.

She is reading from "Craftsmanship", which was eventually published in the essay collection "The Death of the Moth". Inspirational too in putting words on the cartoon, how the seemingly simple line is capable of constant renewal and yet with the many layers within:

"Words, English words, are full of echoes, of memories, of associations. They have been out and about, on people's lips, in their houses, in the streets, in the fields, for so many centuries. And that is one of the chief difficulties in writing them today – that they are stored with other meanings, with other memories, and they have contracted so many famous marriages in the past".

It is the nature of words to change – as it is to the drawn line. So why - to round off with her astonishment at DH Lawrence's project, his criticism of a wide range of persons as being soiled, why not a system that includes what is good? It would have been a true breakthrough: An inclusive system.

The cartoon shown is courtesy of Per Marquard Otzen and must not be reproduced without his permission.