Land of the Unfree

|

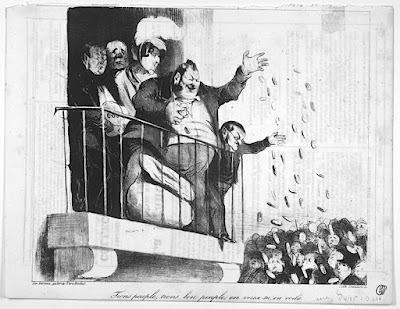

| Honoré Daumier, "Here, good people, here, my people, do you want more? Here you are!" Printed in Le Charivari, April 1, 1835. April's fool anyone? |

"I might as well just re-use my old cartoons!"

Such is the outcry of existential despair when a young cartoonist transgresses the threshold to the domain of the seasoned cartoonists. Latterly the turn came to Khalid Albaih, and he like those who went before him and those who shall come after, found of course no consolation in the knowledge that such is the state of things cartoonwise.

And yes, humankind... but that was the reason for taking up the pen in the first place and well, the presence of strong imagery does have an impact as proved by cartoons of a autocratic ruler from almost 200 years ago.

The father of Louis-Philippe, had been guillotined in 1793. Louis-Philippe became king of the French following yet another revolution, the 1830-one, knowing full well what could happen to his own head and yet he found it intoxicating to indulge the rich to his own gain, covering his autocratic rule under the disguise of a constitution.

The manipulative negligence towards those in need, labeling them as dangerous, dragging in the institutions of the state to do his dirty work and going after the press with every means, using the courts not least, sounds all too familiar today too. An eco-system of corruption:

|

| Honoré Daumier, Gargantua, December 16, 1831 |

The cartoon above cost its publisher, Charles Philipon AND its cartoonist, which was exceptional for its time, six months of imprisonment, about half of which was served at a mental clinic, which allowed them to continue their work. It was at this time too that Charles Philipon drew the king's portrait in court to prove his point that anything can be made to look like anything. Louis-Philippe was transformed into a pear, grasped immediately by the masses present in the court room - by design of Philipon, naturally - and soon pears were graffiti'ed on any wall in France.

The pear is a simple form equating a simple brain. The torso of the king was in no lesser measure of peary dimensions. The higher the number of layers disguising the body in velvets and silks, the more naked he was to the eye of his beholders.

Is there a morale to all of this considering we have yet another pear on the scene?

Louis-Philippe is remembered in history as a mushy pear. He saved his head, but lived his final years in exile - with the enemy. He too was ridiculed for being clownish, but everyone understood what that meant: His rule was constantly exposed; his actions constantly laid out the more they were not meant to be seen.

In the case of The Drumpf, there is one thing his base repeats as if automatons thus contradicting their very words. But let them see themselves in in all of this; let them see that there is a free world and that they are not part of it.

Theirs is the Land of the Unfree.

To witness, Daumier drew Louis-Philippe keeping the free press and oppositional voices at bay, i.e. the mosquitoes and flies by way of issuing laws against both. Oh, behold the free and the mighty!

|

| Honoré Daumier, "The Insect Net", printed in Le Charivari, October 21, 1834. |