"The drawing must be Imagined"

Meïr Goldschmidt, the editor of Corsaren was a constant source of irritation to the Danish autocratic king and in 1844 Goldschmidt was sentenced to 24 days of imprisonment, which brought him recognition as a forerunner in the pursuit of democracy.

His speech defense in court was printed in Corsaren (No, 193, May 24, 1844) of which the central part is to be read below, as per usual my English translation is in italics. Goldschmidt undressed the law on freedom of printed matter by stating how satire cannot be judged by what is implied, only what is actually there - which would of course be impossible since satire never actually states, it implies.

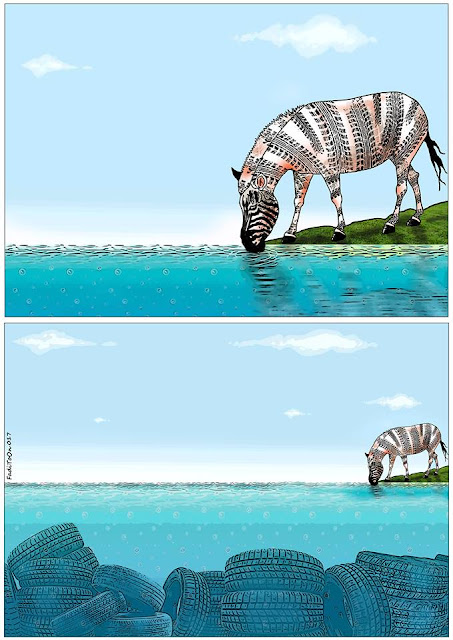

Goldschmidt was furthermore censored for life, a sentence, which was annulled five years later and thereby highlighting the ridiculous tap-dancing of the autocratic rule to retain power, when the Constitution was in place and democracy an actual thing, to paraphrase his juxtaposition. The Danish Constitution celebrates its 167th anniversary today, but the juxtaposition still proves relevant each and every time a satirist, cartoonists not least are standing accused.

|

| "The drawing must be imagined" Peter Klæstrup, Corsaren, No. 198, June 28, 1844. |

"At en forfatter kun bør straffes for de Ord, han har sagt, og ikke for den Tanke, han i dem har udtrykt, og ikke for den Tanke, der mulig kan findes at ligge i dem, er en Sætning, som ikke alene bestyrkes ved Lovens udtrykkelige Bud (at han skal dømmes efter den Mening, Ordene "nærmest og naturligt frembyde"), men følger ogsaa ligefrem af Fornuft og Billighed. Staten kan nemlig som objectiv Existens ikke ville indlade sig paa at dømme den subjective Tanke, men kun Tanken, forsaavidt den fremtræder i objectiv Form, kan altsaa kun ville indlade sig paa at straffe for den Skade, Forfatteren enten har opnaaet eller kunnet opnaae. Hvad kommer det overhovedet Staten ved, hvad en Forfatter eller enhver anden Borger har villet, men ikke kunnet? Villien maa altsaa være aldeledes ligegyldig. Og hvorledes vil man gaae ind i en Forfatters Hjerte og see, hvad han virkelig har villet?

Forsaavidt Retten søger at raade Bod paa denne sidste Mislighed ved at lade Forfatteren personlig afhøre om Meningen af hans Ord, geraader den ind paa en Mislighed af ganske anden Natur. Ikke nok, at den anerkjender Forfatterens Strafløshed ved det samme Middel, hvorved den vil hidføre hans Straf: Den anerkjender, at den lovstridige Tanke ikke ligefrem ligger i Ordene, men først maa bringes derind - ikke nok hermed, siger jeg, men Retten bringer ogsaa Sagen bort fra Trykkefrihedens til Tænkefrihedens Gebeet. Det er nemlig ikke længere det trykte Ord selv, man behandler det er Forfatterens hele Tankevirksomhed. Men, idet man saaledes sætter Tankens foreliggende udvortes Form som det underordnede og søger den fjernere formede Tanke, blive Ordene det reent Tilfældige, og næste Gang kan der ligesaa godt spørges; Hvad har De menet med det Smiil, den Gebærde o.s.v.? Men selv Smilet og Gebærden er underordnet, det er jo Tanken, der søges; man kan altsaa gaae endnu videre og simpelt spørge: Hvad har De meent eller tænkt i det eller hiint Øieblik, eller i det eller hiint Aar, eller i hele Deres Liv?"

|

| The logo of Corsaren by Peter Klæstrup - a pirate's ship with the words of the song "ça ira, ça ira!" of the French revolution. Note how the pirates are greeted from ashore. |

"That a writer should only be punished for the words he has said and not for the thought, he expressed therein and not for the thought that could possibly be found to lie therein, is a phrase, which is not only corroborated by the express command of the Law (that he shall be judged by the opinion "posed naturally by and following from" the words), but it adheres to reason and fairness. As an objective existence the State cannot engage in judging the subjective thought, but only the idea, inasmuch as it appears in an objective form and can thus only engage in punishing for the damage that the author has either brought about or been able to bring about. What is it even to the State what an author or any other citizen wanted, but have not been able to? The will must therefore be utterly without signification. And how is it even possible to enter a writer's heart and see what he really wanted?

Insofar as the Court seeks to remedy this last irregularity by letting the author be interrogated in person on the meaning of his words, it is bound to encounter an irregularity of quite a different nature. It recognizes the impunity from prosecution of the author by the same means whereby it will punish him: It recognizes that the illegal thought is not exactly located within the words, but must be placed there first - and not just that, I say, but the Court moreover brings the matter away of from the matter of the freedom of the press to the freedom of thought. It is thus no longer the printed word itself, which is its concern; it is the entire thinking sphere of the author. But when the present external form of the thought is classed beneath the distantly shaped thought, the words become purely accidental, and the next time it may just as well be asked; what have you meant by that smile, that gesture and so forth? But even the smile and the gesture are secondary, it is after all the idea, which is sought; one can therefore go even further and simply ask: What have you meant or thought in it or that moment, or in this or that year, or in all of your life?"