Do We Need Stereotypes?

|

| Christoph Niemann with his example on how to minimize the population of baby pandas. Screenshot from his TEDtalk, August 2018. |

The stacking of pictorial elements such as the suit, the ladder and the dollar sign into an "And then... and then... and then...". All telling and no showing. It might as well have been written. There is a reason, why it is a safe blanket for editors, as Niemann points out, in that no one will notice the presence of the cartoon.

Niemann took a stand against what I call lazy cartooning and it is an important one, since this is what gives cartooning a bad name. I wish to take his words one step further and address the lazy way we talk about cartooning, i.e. the tired litany that cartooning runs on stereotypes.

When we speak of premises for composing a cartoon, we do not speak of a repertoire or even just motif the way we classify the workings of other art forms. Instead, we speak of stereotypes, which in its meaning comprises the form as well as its content. A stale idea from beginning to end from which arises nothing but a travesty: a mockery of all that is artistic creation and by thus intelligent life.

The life of lazy argumentation is made all the easier from the fact that cartooning uses figuration. Such as fish, bears and the Statue of Liberty. Well then, the line of argumentation seems to take, every time there is a bear, that is... seen before... But cartooning is not primarily about the seen before.

Cartooning is what it brings to the conversation with us, its beholders.

|

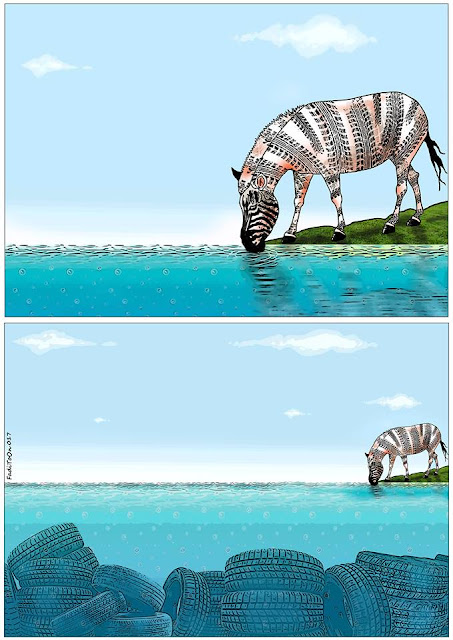

| Riber Hansson, 2007. |

The danger of even looking this bear into his eyes.

Before us - right above and below - are two of the most drawn symbols on power and freedom respectively. They come from each from their corner of the world and they each specify how their respective nations define themselves or are defined.

Let us speak of Ur-Stories.

Art forms have their Ur-Stories onto which every new artwork adds another layer. The two symbols before us are effective in that the one above contain a long story of killing fields, defeating both Napoleon and Hitler, because the latter ignored the lesson Napoleon was given. There is a myth to that power of something impossible to fully grasp however much we try.

Below is the Roman goddess Libertas in her best-known recent configuration as the giant in bronze correlating to the giant idea of freedom. Goddesses and what they personify along with the powerful animals are imagery on the grandest scale from the equally grand compositions of history painting once commissioned for palaces and later on for town halls and parliaments.

Here someone will immediately object that regal history painting is no longer relevant and there is a reason why. However, there will always be ample reason for the artist taking on history, as Aristotle confirmed. The artist creates something that we can encompass with our eyes. A dramatic mise en scène that encompasses all that has taken place and what is likely to happen from here on.

Aristotle gives us the fine-tuning explanation on what the cartoonist does when using figuration. The solidity before our eyes is based in abstraction. The artist selects the traits of our day and age and deducts from there what will reasonably take place. In the dramatic narrative that ensues, we see the characters how they are likely to speak or act.

We recognize the characters. We recognize their arguments. We recognize it all because this is our world; an observation that was true, when Aristotle wrote it just as it is today. We are part of what is taking place before us and we see it all come alive.

Portraiture is a key feature to the drama. In fact, a portrait can be so deftly composed that it encompasses it all. Riber Hansson has drawn a specific danger. The one that seeks to stifle truth and democracy alike. Putin is replacing the many voices of democracy to the one before us. His narrative only. He his challenging us, securing our gaze to let us know just how dangerous his game is. His file is just for show. He is his own weapon and his portraitist has undressed him to his fur.

There is a narrative to win back from the narrative of Putin and his lackeys around the world, one of which is orange. Siri Dokken has dissolved the Drumpf into orange gasses interspersed with willowy yellow. This is a composition on a juxtaposition that is no longer there. The bronze has been eaten from within and is now collapsing to one side, while the gasses are unraveling to the other. The only vertical line left is the IV stand. Liberty is nothing but a skull whose skin has dragged the ear down to one side. That is a badass detail of the most painful nature.

The eyes of the bronze has slit open to the despair beyond all despair.

It is not healthy looking into her eyes, just as it is not healthy looking into Putin's, but "We need to be involved in the argument if we are to have any chance of winning it", as Salman Rushdie wrote in the The New Yorker in May on the anti-truth times in which we live.

Our cartoonists have given us the punch in the stomach to do so.

|

| Siri Dokken, August 23, 2018. |

The cartoons shown are courtesy of Siri Dokken and Riber Hansson and must not be reproduced without their permission.