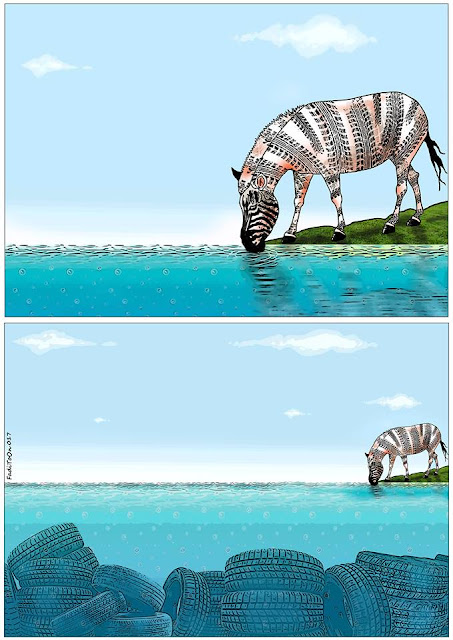

When It Goes Bad, It Grows Poisonous

Pages for a new History of Political Cartooning in Denmark

The dread of the French presidential election is upon us and let us time travel back to the French-Prussian war 1870-71, when tension and change in society all over Europe led to Nationalism and anti-Semitism, two of the worst factors in European history.

Let us do so through the Danish satirical magazines of the 19th century we have noted on this blog for their clear voice against the corruption of democracy. Sometimes they are rightfully scorned as silly nothings.

Not just that. When they are at their most superficial, they are not just poor in quality. They become a means to undermine democracy.

This for one is a prime example on poor cartooning:

Let us do so through the Danish satirical magazines of the 19th century we have noted on this blog for their clear voice against the corruption of democracy. Sometimes they are rightfully scorned as silly nothings.

Not just that. When they are at their most superficial, they are not just poor in quality. They become a means to undermine democracy.

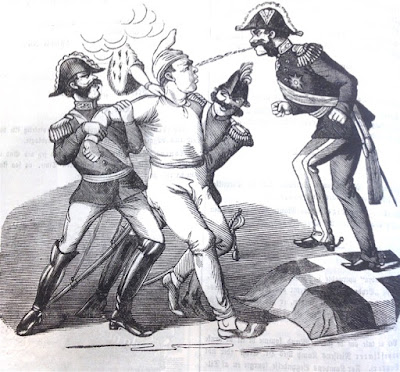

This for one is a prime example on poor cartooning:

|

| Peter Klæstrup, Folkets Nisse, No. 19, May 8, 1869. |

The archetypal Dane, alias Mr./Hr. Sørensen mocked by mightier powers of which the arm of Queen Victoria is keeping him in place to be spat on. The flag is trodden upon, but Mr. Sørensen's back is straight and his head is held high. He is even looking his spitting opponent in the eyes.

We know the formula all too well. An apparent victim, whose victimization has an inherent violence to it by way of inciting anger in the beholder.

The whole point of Mr. Sørensen is furthermore turned upside down. He was never meant to be a hero. On the contrary, he was everything the citizen should refuse to take after. He was calling to action in the name of democracy by way of lacking the energy to do so. If he represented a nation, it was for all that was wrong within its borders.

Consequently the outlook of the editorial group would possibly undergo dramatic change around every new term at uni or so. By 1867-68 the magazine would run mock examinations, cite half-digested learning and proudly strut the Latin name for a flea, pediculus.

its sting would have been magnificent.

Interestingly, the visual side of the magazine grew just as stale even if the cartoonist remained the same. No donkeys for chamberlains for one. No human transformations. Instead attempts were made such as creating a shorthand for the Prussian Chancellor Bismarck with three strains of hair standing on edge on his scalp. Drawn upon the already outlined scalp, the three hairs evolved into nothing.

A feared neighbour was constantly headlined as an enemy as in the one below on Bismarck forcing the Danish editors to laud the Prussian king on print or... It was of course not directed at Prussia as such. It was the students' immature way of declaring fatigue of reading up on the classics from "German Civilization".

There were scaffolds everywhere in cartooning of this time as a warning to anyone in power threatening to undermine democracy and directing their means at themselves.

This one has no intention in life, but "daring" to question the classics.

|

| Peter Klæstrup, Folkets Nisse, No. 35, August 27, 1870. Folkets Nisse, i.e. the Elf of the People taking the noble stand of refusing... Cartooning as self-congratulatory propaganda. |

Anti-Semitism was latent in society and hints of it would surface from time to time in the satirical magazines. However, by the time we get to 1868, anti-Semitism was not just showing its ugly face, it was basking in it.

Let us return to the poor I.W. Heyman; he who had a hard time being drawn after receiving his Knight's Cross in 1865 and chose to pay to halt the attention on his person. That in turn made him a constant ridicule in other satirical papers, but in 1865 not for his religious background.

That had changed only three years later, when much was made of the weight of "bearing his Christian cross".

In 1871 he was elected town council member, while a new bright name was in town, the colorful G.A. Gedalia. A successful businessman from a humble background, Gedalia had bought a couple of honorary titles abroad, one of which was the title of baronet, bought in San Marino in 1870.

If only he had bought it a few years earlier! What a feast it would have been cartoonwise. Instead, Gedalia became a household name at a time, when his aspirations would be spun around his Jewish background.

A few years later Folkets Nisse was back on track, or it was for the most part a better one, but let us go back in time and reflect upon what had been forgotten or lost.

hints were made that as the owner of a number of properties he let out, said properties was or might have been in a sorry state.

Of the truthfulness of this we can only guess and if true it was certainly nothing specific to his properties. On the contrary, it was the norm of the day and would be so for another two to three generations.

|

| Peter Klæstrup, Folkets Nisse, No. 78, September 4, 1852. |

Only, seeing the poor exploited, who had no other options, the magazine found it was its duty to speak up.

The present cartoons were presented as an invitation for the council dedicated to improve housing in Copenhagen to visit the marvels of Nørrebro, one of the poorest parts of town and of which the main thoroughfare alone must be of prehistoric value considering the state of it, as Folkets Nisse pondered, since what else could be the reason?

|

| Peter Klæstrup, Folkets Nisse, No. 78, September 4, 1852. |

Not to mention the hovering gate of Blaagaard No. 46, making a point of not mentioning the name of the owner, since he was "so modest". Folkets Nisse underlined that whoever built it was no longer known, the present owner was, however. He, whose duty it was to keep it in habitable shape.

|

| Peter Klæstrup, Folkets Nisse, No. 78, September 4, 1852. |

Everyone would have known the name of the owner or be curious to know and create for a situation, in which questions on his name would come up. He was not shamed, however, the present marvels of buildings hardly holding up were presented as examples of a much larger problem, calling for inspection of relevant commitees of "aesthetic interest".

That was Folkets Nisse at its best. This was when they worked to make a difference, placing its sting by way of playfulness. A serious problem was visualized by means that were aggressive, not vindictive as the ideal is characterized in today's political climate. Or, as its motto was in the first years of its existence: "Et Værn mod Forurettelse er Pressen":

The press is a safeguard against grievance